Adaptations, specifically video game adaptations, are a tricky business.

Change too much, it becomes unrecognisable. Change too little, and it’s a copy-and-paste of something everyone’s experienced. The delicate work comes in finding space and time to expand without feeling unnecessary. With ‘The Last Of Us’, there’s ample opportunity for this. The 2013 game was, narratively speaking, a relatively simple journey. You took on the role of Joel, a hardened smuggler surviving in a post-apocalyptic America that has been ravaged by a virus that turns people into horrific ‘clickers’. The few human settlements that remain are either under the control of FEDRA, a government disaster agency turned military dictatorship, or autonomous groups of varying levels of desperation. Joel is tasked by a band of rebels called the Fireflies to help lead a young woman - Ellie - to a hospital where her immunity to the virus can be investigated and used to make a vaccine.

In the TV adaptation, it’s pretty much exactly like that. Yet, showrunner Craig Mazin, together with the game’s creator Neil Druckmann, has used these bare bones to flesh out the story with real, human stories of survival and hope in a world that’s short on both. One episode, in particular, is strikingly emotional, in that it entirely pulls off the main route of the series and diverts to a romantic relationship that develops over twenty years involving ‘The White Lotus’ alum Murray Bartlett and the ever taciturn Nick Offerman. Later in the series, there’s a two-part arc involving a collaborator in hiding that joins up with Joel and Ellie to escape a city on the verge of collapse, both real and symbolic. Over the course of nine episodes, ‘The Last Of Us’ brings us into a very real world - emotionally and visually - without it ever feeling like it’s being burdened with bloat.

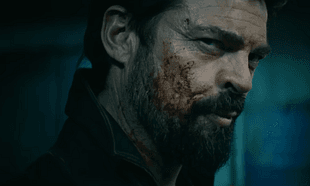

In saying that, ‘The Last Of Us’ makes time for Pedro Pascal and Bella Ramsey to find their dynamic over the course of the series. The trust - if trust can exist in a world like this - takes time to build and is earned slowly and broken easily. What’s more, there’s a real sense of how differently the two characters have developed since the end of the world, or rather after it. Pedro Pascal’s Joel is haunted, as he’s seen the world before and the world after and knows what’s been lost. Bella Ramsey’s Ellie, on the other hand, is cynical and dismissive. Yet, beneath this, there’s an undercurrent of hatred and rage that bubbles over at various points that makes for some horrifying moments.

Compared to ‘The Walking Dead’, there’s a clearer and neater passage through the story here, and it isn’t necessarily burdened by the expectations of explaining every last thing. In the opening beats of a couple of episodes, we grasp just how inevitable the virus is and how it came to destroy the world in a matter of days. The collapse of civilisation that follows is equally inevitable, and doesn’t require entire seasons to develop and explain. Moving back and forth in time is done with care and the distinctive visuals mean it’s easily understood. Even small touches - everyone looks like shit in the post-apocalypse, as they should - help this point. From a production design standpoint, ‘The Last Of Us’ doesn’t care to make anything look particularly cool just for the sake of it. Nobody’s carrying samurai swords, everything is either scrounged or improvised.

Told with care to its source material but with tasteful embellishments and refinements, The Last Of Us’ may not be necessarily unique, but its emphasis on human stories in an inhuman world makes it so.