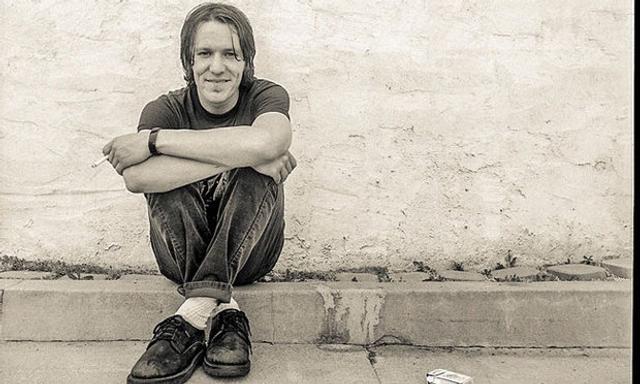

October 21st 2013 marked the tenth anniversary of the death of one of greatest songwriters of his generation. In his short life, Steven Paul "Elliott" Smith compiled a body of work that looks set to endure; his songs of fragile, luminous beauty appealed to those who grew to know and love his music in a very unique and personal way.

Portland based writer William Todd Schultz has just written what looks likely to become the definitive account of the life and music of Elliott Smith. 'Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith' is a fascinating, compelling and well researched biography taking us right through from his troubled childhood to his tragic death at the age of thirty four. Todd took some time out to talk to entertainment.ie about writing the book, Smith's struggle with depression and the circumstances surrounding his tragic death.

Note: The second part of this interview will be available from Saturday 25th January. You can buy Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith at this link.

You can read part two of this interview here.

Words & Interview by Paul Page

Congratulations on the book Todd, it's a fascinating read and a very thorough examination of the life and music of one of the greatest songwriters of the last 30 years. When did you personally first encounter the music of Elliott Smith?

It's hard to date these things since they sort of sneak up on you, but probably about a year before I started the book. My daughter went to the same high school as Elliott did, Lincoln High School in downtown Portland (where I still live now). She started getting into his music, listening to it more or less non-stop (after a similarly intense Shins phase), and I kept overhearing what she was playing in the study of our home. I couldn't believe it. I was astonished. Every song--every single one--was so absurdly good. At the time, I'd finished two books, and I was reeling about for what to do next. And bit by bit, day by day, I grew more and more captivated by the possibility of writing about Elliott. Finally one day I decided--let's do it. It's funny. I floated the idea to my agent. At first she was ho-hum. So there was a moment, lasting a couple weeks actually, when the idea sort of languished. Then my agent came around, and my editor too. I told them both Elliott's story, and they saw the potential.

One of the things that really screams off the page is the effect Elliott had on the lives of those he knew and worked with. So many people seemed to love and care for him during his lifetime. What was it about him do you think that engendered that depth of feeling?

It's a very good question. JJ Gonson told me it was impossible not to love Elliott. But why? I think, for one thing, people were mesmerized by his talent, maybe first and foremost. The kind of thing that happens with all great artists. We want to know them. We want to be close to them. They move and inspire us. We aspire to be like them. We want to know how they do it. But a lot of his irresistibility also had to do with his personality. He was, at least for most of his life, before the terrible drug addiction phase, a compassionate, humble, honest, outrageously intelligent, loving person. And his vulnerability came through; he was a vulnerability genius. He didn't hide it. People could see there was a wound there, something deep. So because of his humility and grace, people found it easy to sympathize. They wanted to help or save him, chiefly from himself. This dynamic played out pretty clearly in a lot of his love relationships, it seems. Finally--and I try to emphasize this in the book--he was fucking funny. In a sly, artistic, sideways fashion. The myth is of Elliott as this comically fragile, sad sack buzzkill. But that's not accurate. He was a huge clown.

Was there any reticence on the part of friends and family to co-operate with you on writing the book? A sense that they still needed to protect him even in death?

Definitely. And it was totally understandable. I always respected whatever decision people ended up making. I never tried changing anyone's mind about talking to me. In retrospect, I possibly could have been a bit more pushy. Most biographers are. But that's not who I am, it goes against my nature. And the whole subject was very delicate, largely because of the manner of Elliott's death. What I don't think a lot of people understand is that biography is a total immersion in a universe. It's not only about the subject, but all the times and places, friends and lovers, various Zeitgeists (from Portland to LA). It gets to be oceanic. Meaning is context-bound and context is boundless. Yet in the end you are a story gatherer. And that requires people sharing stories. I was lucky. A lot of people talked to me who had never talked before. Or they went into more detail than they had before. For my part, I was conscious of being honest, respectful, clear about my aim, sympathetic, totally open, willing to answer any question. I came to be friends with some of the people I met and talked with. And for that reason and others I carried through every single line, every single word, a terrific sense of responsibility--to Elliott and to his friends. It turned into an immensely personal, emotional project for me. Are there people I wish I could have talked to but didn't? Yes. But that seems inevitable. And I feel as if I talked to enough people, important people, to construct a credible portrait. I should add: there were at least 30 hours of off-record conversations. I don't cite everyone I spoke with. Some talked under the condition of anonymity.

A lot of his subsequent difficulties and the depression that dogged him in his adult years seem to be traced back to his childhood, and in particular his fraught relationship with his step-father Charlie. There is a veiled suggestion from various friends that some kind of abuse was involved, yet even Elliott himself wasn't sure if this had happened. What is your take on this?

It's impossible to be sure. I simply don't know. I tried to be very, very careful about that topic in the book, and I leave it an open question. On one hand, some of Elliott's memories might have been false. He thought so himself. In the last year of his life he wasn't reasoning all that clearly. Drugs had left a residue of paranoia behind that was very adhesive. So it's tricky. On the other hand, it was definitely a hard, difficult relationship. There could have been emotional abuse, of some sort or some degree. And Charlie shows up in the songs--sometimes by name, sometimes not. So artistically, Elliott returned to that theme, that character, and it seems he must have done so for a reason. It was emotionally unfinished, maybe. It was a trauma he was trying to exorcise. Depression was a character Elliott played, and over time he played it more and more, and it may have killed him. I'm not saying he wasn't literally depressed--he was. But he made suffering a major part of his identity. In fact, fans came to see that aspect of him, especially in later years. It could be gruesome. They wanted to watch him suffer, and to feel redeemed by his honesty. As JJ Gonson told me, he was in love with depression. He felt it was necessary for the music. Even when he first tried antidepressants, he did so reluctantly. "If I'm not depressed, then who am I?"

One of the things that really struck me in reading the book was how easy the music came for Elliott -it was the living part he found difficult. The songs seemed to flow, and this continued right up to his death. Do you think that in some ways his unhappiness was the fuel he needed to write as prolifically as he did?

It's the case for a lot of artists, especially the ones I write about. Darkness is the muse. As Elliott said in an early draft of King's Crossing: "The big problem is the main attraction." He was drawn to the pain. And he made the art out of it. There's that great line by the poet Philip Larkin (whom I adore): Happiness writes white. The sensuality of melancholy seems to deepen and inspire the creative impulse. I am certain Elliott was aware of this. I'm sure he'd agree with Larkin. There's an interesting side-question here: Does creativity help you to overcome or is it just more agony expressed symbolically or metaphorically? One sort of decides on a case by case basis. I've always felt that art is NOT intrinsically therapeutic. It can be, but not necessarily. What I think music-making gave Elliott was a feeling of enormous satisfaction and power. We enjoy doing anything we know we are good at. But it definitely didn't solve his problems. They were too comprehensive.

The second part of Paul Page's interview with William Todd Schultz covering Smith's Academy Award success, his heroin addiction and the circumstances surrounding his tragic death is available here.