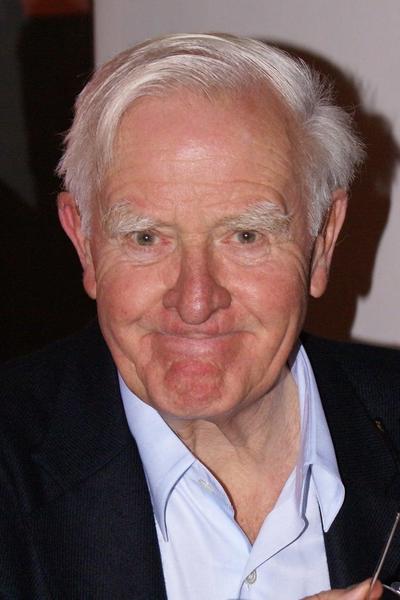

Told through a series of interviews, John le Carré - bestselling author of 'Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy', 'The Spy Who Came In From The Cold', 'The Looking-Glass War', and 'Smiley's People' - discusses the nature of his working life in the public eye, and his fractious and difficult relationship with his father, a serial gambler and con artist.

For anyone who's read John le Carré, there's a grim delight in the seediness of it. The characters in his novels and the subsequent adaptations are not prone to wearing tuxedos, nor do they finish off a kill with a satisfying pun. There are precious little gadgets, and there's not even a car chase or an explosion to enjoy. Instead, le Carré explores the emptiness and the perversions of people who survive through deceit and excel through deception. None of his characters are what one would call desirable or heroic, yet they are nonetheless real, fleshed-out characters. Yet, for all of the notability and the depth of these fictional people - George Smiley, Magnus Pym, Bill Haydon - what is there in them that is of John le Carré?

The opening scene of 'The Pigeon Tunnel' finds the author - real name David Cornwell - in direct conversation with Errol Morris. He speaks candidly, openly, about how he's watched some of Morris' work and wonders what kind of presence he'll be in this very movie. Will he be the all-seeing, all-knowing voice or will he be more investigative? The question is never fully answered, and much of 'The Pigeon Tunnel' is wrapped up in mysteries and falsehoods. The author is frank about his father, and how he was prone to intervening in his young life to push him towards upper-class English endeavours. As is eventually revealed, his father was a charismatic con artist who was frequently making and losing fortunes until it eventually caught up with him. Even when he becomes vastly wealthy through his writings, there's a kind of emptiness in it for Cornwell.

Morris smartly deploys scenes from some of the adaptations and layers them into Cornwell's recollections. Scenes from 'A Perfect Spy', starring our own Ray McAnally as the thinly veiled stand-in for his father, overlay his memories. Later scenes jump to news archival footage when Cornwell discusses his time in MI5 and MI6, and specifically, the long shadows of the Cambridge Five and his own recollections of Kim Philby. Again, Cornwell is candid - probably too candid for his own good - about Philby, and about how he could empathise with the nature of a double agent and a traitor. Indeed, Cornwell points out that Philby was not the former - but the latter. More than that, he speaks earnestly about his regrets as an author - and how he made the British intelligence services appear competent, far too competent in his mind.

'The Pigeon Tunnel' is a unique, sometimes frustrating take on a documentary portrait. It's no surprise that Cornwell's interviews are sometimes done at a distance, or very often with mirrors surrounding him. We're never able to get terribly close to him, even though he is receptive and willing to speak on just about any topic that's put in front of him. Morris, for his part, does his utmost to try and unearth elements of the author that have long been buried and hidden. Instead, we find that the reason it has all been so well hidden is that there is a gnawing, gaping emptiness. Cornwell often talks about an empty room being at the centre of the universe, but perhaps it was the one he created in himself.