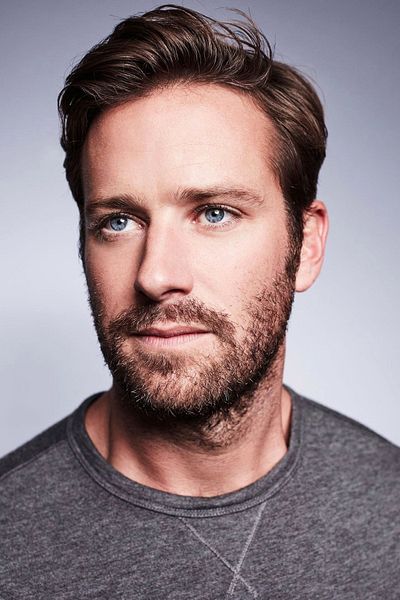

Taught to read by the kindly wife (Miller) of a plantation owner, Nathanial (Parker) grows up to become a preacher whose sermons of peace and love are used by other slave owners to keep their slaves in line. As he travels the state with former childhood friend Samuel Turner (Hammer), now his debt-stricken owner, the horrors Nat witnesses changes the biblical words of determination to another meaning: a day of reckoning will come.

This remake of the D.W Griffith 1915 classic rights the wrongs of the original. Written, directed and starring Nate Parker, this true story, based on the events surrounding the 1831 slave rebellion, jettisons Griffith's KKK as a heroic force quelling a slave rebellion, while the role of Nat is boosted to an almost a Christ-figure, told he is destined for greatness by a prophecy and gathering his followers through the teachings of the Lord. White men are definitely the bad guys - murderers, rapists, paedophiles; some are even Jackie Earle Haley, a slave hunter of mean temperament. Hammer's Samuel is fond of Nat, detesting the institution of slavery, but as he loses himself to alcohol and debt he becomes too weak-willed to do anything about it.

It's an assured debut from Parker behind the camera (he turns in a strong performance in front of it too) but his script can be a bit hasty at times. Skipping through the years – Nat is a boy, then a preacher, a preacher who woos and marries Cherry (a wonderful King), and has his Damascus moment in what seems a very short time - gives the story a momentum it probably wouldn't have, but this zippy pace diminishes the impact of the rebellion itself: everything that has gone before has been building up to this moment and it just whizzes by.

Parker frustratingly dodges some scenarios that would tighten his film: with Hammer's Samuel treating his slaves humanely, it's left to Jackie Earle Haley to be the chief antagonist but he drifts in and out of the story. It's also put to Nat that he uses the bible to justify violence ("He's a God of love – don’t forget that.") but that duality isn't explored, nor is Nat ever challenged on the notion that God has abandoned his people.

Parker may skip through his big moments but he certainly is in command of the visuals and drums up some striking imagery: the gentle swop over the cotton fields at dawn, the whip that moves like a snake as it is dragged through the leaves, the terrible solution to a slave's hunger strike, and, in one of the most haunting shots of the year, slowly tracking through a treeline to Nina Simone's Strange Fruit as men, women and children hang from branches.

This remake of sorts (Parker says he used the title ironically but with design) shouldn't be a timely one but it sadly is - one hundred years after Griffith’s film and initiatives like Black Lives Matter and films like this are still necessary.