A deeply personal coming of age drama from Japanese writer-director Naomi Kawase, Still The Water is occasionally touching but the ponderously slow pacing halts any real emotional investment.

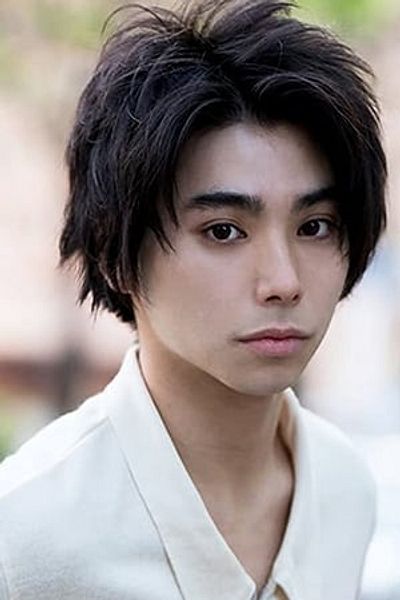

Two sullen teenagers - Kaito (Murakami) and Kyoko (Yoshinaga) - find they have something in common when a man’s body is found on the beach. The death shocks the town and brings into focus what is happening in Kaito and Kyoko’s homes. Kaito’s world is forever in flux. A child of a divorce - his father lives in Tokyo and his mother either at work or entertaining new boyfriends - Kaito yearns for some stability. Kyoko experiences the opposite, staring an awful permanency in the face - her terminally ill mother has returned home from hospital to spend her last days with her family...

Kawase opens with crashing waves before cutting to a goat getting its throat cut. This is the struggle that plays out here: the waves that perpetually pound the shore representing infinity, the killing of the goat the stark inevitability that everything comes to an end. But Kawase isn’t bold in addressing this, burying the theme in her mumblecore dialogue. At one point Kyoko’s father remarks that the banyan tree in the garden is four or five hundred years old, and later we see a crane mercilessly pull trees down. Score one for the nothing lasts forever side.

But then there’s the rebuttal. The insecure Kaito is told by his father that while everything is transient, there’s one thing that will never change: he will always be his father and Kaito will always be his son. This realisation brings a rare smile to the teen’s face - perhaps there are things that one can depend on. Later, Kaito rebukes Kyoko’s offer of sex, perhaps in the misguided belief that in refusal he will stay a boy forever.

While watching this play out is interesting, the slow pace undoes all the good work with Kawase dragging out scenes long after their use has expired. And her teens in her teen film aren’t believable. With their introspective philosophical musings, they don’t sound like sixteen-year-olds. And they needed to be. They were our way into the story but Kawase makes them inaccessible beyond the trouble-at-home trope.