John Boorman has led an interesting life – from surviving the Blitz to making it in Hollywood during the golden era of the late sixties/early seventies, his is a story rich in incident. Unfortunately the story of Queen and Country, a belated sequel to his 1987 Oscar-nominated Hope and Glory, turns out to be the least interesting episode of the writer- director’s life.

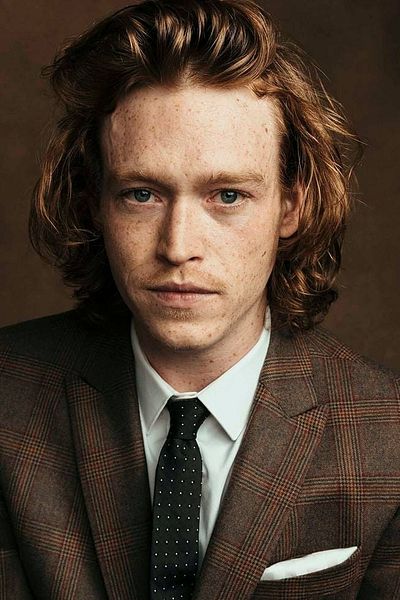

Boorman’s alter ego Bill Rohan was only nine when Hitler’s bombs fell on London in Hope and Glory, but now he’s a twenty-year-old sergeant (played by newcomer Callum Turner) teaching recruits typing skills before they are shipped off to Korea. When not fending off unpatriotic accusations from top brass and MI5, he and best friend Percy (Jones) delight in winding up uptight officers like Digby (Brian F. O’Byrne doing his best barking, swagger stick tucked under the arm Sergeant Major thing). He eventually falls for the posh Ophelia (Egerton) and something approaching a plot happens by.

While this all the earmarks of a very personal story there’s no escaping the episodic nature of the plot, loosely strung together by the friendship between Bill and Percy and the romance. Typing doesn’t make for exciting visuals but it’s the clichéd love affair that drags the film down. Boorman opts for the tried-and-tested 'she’s beautiful ergo cruel' tactic - which makes you dislike her and him for wanting her - and their dialogue feels stiff and written: "My room is a mess… but so am I."

When not getting bogged down in the melodramatic love affair, Boorman veers from playfulness – peeping through windows to watch women undress, the knockabout Dad’s Army antics – to tackling serious issues – Thewlis’ twitchy Sergeant-major succumbing to post traumatic stress disorder.

This is where the film is at its strongest. David Thewlis, emerging as the villain once the story forgets about Byrne for a while, manages to get something from the material. But then he’s the one written with any kind of depth - a man who has given his life to the army and unwilling to entertain the thought that it has given little back. Bill and Percy’s torment of him turns them into the villains of the piece, which I’m sure is not Boorman’s intention. Turner meanwhile is hemmed in by a very straight role and so Jones overcompensates with an ants-in-my-pants performance. Pat Shortt has little to but skive about.

Hopefully Boorman won’t wait as long again for the third instalment in Bill Rohan’s life – the first steps to becoming a director.