The story doesn't need smatterings of sentimentality or three-act-structure or any other kind of device to get its point across, or to capture the horror of what happened

Detroit, 1967. After a police raid sparks off riots across the city, a trio of police officers (Will Poulter, Jack Reynor and Ben O'Toole) and a contingent of soldiers from the National Guard take several people hostage at a hotel - believing one of them to be a sniper.

Very often with films based on a historical event, drama sometimes needs to be injected into the story in order to make it more believable for audiences or palatable to their sensibilities. In some cases, bringing the structure of genre to bear on it can help to wrangle in the eccentricities of a real-life situation. Very rarely do you see a film that gives a honest account of something, instead relying on storytelling tropes to make it more easy for audiences to follow. Detroit doesn't have any of that. Instead, what Kathryn Bigelow does is present a full account of what happened in the Algiers Hotel on the night of July 26th, 1967. The story doesn't need smatterings of sentimentality or three-act-structure or any other kind of device to get its point across, or indeed to capture the sheer horror of what happened.

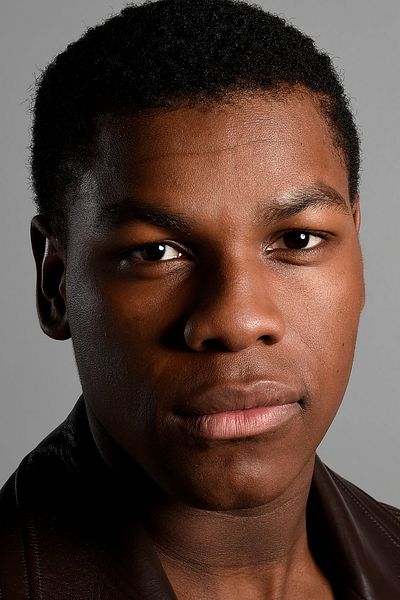

The film opens with a slightly jarring sequence of animation that details the social context that led up to the riots. From there, Kathryn Bigelow's frenetic, handheld style of filmmaking kicks the story off with showing the initial raid on an after-hours club that sparked off the situation before it cuts to newsreel footage of the ensuing riots. The opening act moves between John Boyega's character, Dismukes, holding down two jobs - one of them as a stonemason, the other as a security guard for a store - and Will Poulter, Jack Reynor and Ben O'Toole, three trigger-happy rookie cops who are patrolling the streets with shotguns and an unflinching belief in white supremacy. The stories begin to intertwine when a musical group, led by Algee Smith and Nathan Davis Jr., decide to hide out in the Algiers Hotel as the rioting around them intensifies.

Before long, the National Guard and Poulter's trio arrive at hotel with the intent of tracking down a sniper they believed fire on them earlier in the night. Initially, one would be forgiven for thinking that the film is going to be something like a siege thriller, or perhaps an award-friendly drama of hope over adversity. When the film comes into its second act, these preconceived notions go out the window and we're shown the brutality and viciousness of what it's like to be black in America. The ensemble performance, from Anthony Mackie, John Boyega, Will Poulter, Hannah Murray, Algee Smith and Jacob Latimore, are natural and unfiltered, all of which adds to the terror that just radiates out of the screen. Likewise, there's no poetry or resonance to any of the dialogue - it's clunky in parts, there's no sense of theatricality or verbosity to it; all of which adds to the realism.

It's only in the final act that the film begins to feel like it's sagging, showing the aftermath of the events through a trial and where one of the survivors struggles to reconnect with the world around him. While it's understandable why Boal's script detailed and Bigelow filmed it, there's a sense that it could have cut out of the final cut for a sharper, more concise film. Moreover, it hammers home several points that were well and truly driven in earlier. Bigelow's use of handheld camera adds a realism and authenticity to what we see, but it also gives the film a speed and sense of movement for what's essentially a hostage drama. In the hands of another director, it would have very easily been made into a completely different film with a far more duller edge to it. Here, Bigelow cuts deep and fast into the racial tension in America by laying out the facts as dispassionately as possible. This in turn makes for a much more visceral response when you're watching it; you're not being told how to feel or how to react. Anyone with the slightest sense of right and wrong could watch this film and get it.

By the time the credits roll around, it's clear that the story is pointing towards the current situation in America and how little things have really changed, and how systemic and ingrained the violence is within American society. It's hard not to come away from Detroit feeling equal parts enraged, disturbed and saddened - and even more so when you realise that the problems faced by those on screen still happen to this very day. Overall, 'Detroit' isn't an entertaining watch, but it's a necessary one.