While there's all sorts of superlatives attached to a film like Blade Runner - transcendent, ahead of its time, revolutionary - Ridley Scott was, at the time of its release, less than enthused.

The troubles on set are well-documented, but one point Scott made in the excellent documentary Dangerous Days was how being ahead of its time was almost as bad as being behind the times. Blade Runner was ahead of its time in 1982, that much is clear. In 2017, thirty-five years later, it's still ahead of its time and only certain aspects of the story and plot are beginning to catch up with humanity.

Broadly speaking, Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick's source novel Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? was concerned with being human - and what we define it as. Roy Batty, Rachel, Zhora, even Harrison Ford's character, Rick Deckard, were struggling to gather up enough reason and meaning as to what life meant - and, ultimately, it was that struggle that made them human. Roy Batty's desperate attempts to elongate his lifecycle is the very essence of humanity. He was afraid to die, and was willing to kill his own maker in order to express his feelings of impotent rage.

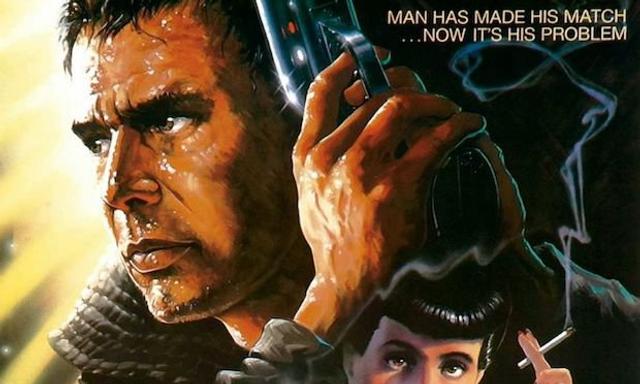

In 1982, this was heavy stuff - and, unsurprisingly, it didn't go over with audiences of the time. The first trailer tried to make Blade Runner seem like some sort of summer sci-fi blockbuster in the vein of Star Wars and positioned Harrison Ford, dressed in a trenchcoat, blasting away and getting his lights punched out to the tune of thumping synthesisers. Posters screamed about the director of Alien and the star of Raiders Of The Lost Ark teaming up for "a spectacular journey to the savage world of 2019", with Ford wielding a futuristic-looking pistol over a cityscape.

UK lobby poster for Blade Runner

In the same summer, Blade Runner had to contend with E.T., The Thing, Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Tron and Conan The Barbarian. The summer was ruled by E.T., but history's been far more kinder to the ones that didn't make it. Yet, for all the issues with Blade Runner and the two official cuts of the movie that followed, there wasn't a huge amount of difference between them. The basic structure of the story was still in place, the same emotional beats and the overall theme is still the same as the one that hit cinemas in '82.

Hindsight's a great thing, of course.

If anyone knew what they were seeing, and how revolutionary it was, people would have stood up and noticed. The studio marketing would have been the same as well. Blade Runner, by any definition you care to put on it, is not a summer blockbuster. It's not even a blockbuster, though it has all the trimmings of it and maybe that's why the studio marketing didn't work for it. In fact, this very point was what perturbed critics and audiences when the film was released. They were being sold an action / adventure film, and instead got a dense, thoughtful sci-fi drama about the very meaning of life.

Even though Blade Runner was subsequently and correctly reevaluated as one of the best sci-fi films ever made, the initial box-office failure definitely contributed to major studios becoming more and more averse to taking risks. In a way, it's nobody's fault - although it's easy to point and blame to marketing executives' lack of imagination for not making Blade Runner more of a success.

Look back over Blade Runner and try to sell it to a large audience the way a studio would. The first gun-shot is fired about fifteen minutes, and another one isn't fired for another forty. There's endless scenes without any kind of dialogue, and while the special effects are mesmerising, it's all pushed into the background. Harrison Ford's usual charisma and laconic wit is stripped away and replaced with a portrayal of a damaged, lonely man. Aside from him, none of the other actors were well-known. Blade Runner was Rutger Hauer's second American film, whilst Sean Young was known for Stripes, a comedy with Bill Murray, and Jane Austen In Manhattan, a Merchant-Ivory film that had a small theatrical release in the US. This was Ridley Scott's third film, his second being Alien - which was lauded for its thrills and scares, as well as being commercially successful.

When you add that all up, it's no wonder Blade Runner's marketing then didn't work. But, in a way, the failure to market Blade Runner correctly or effectively helped to add to the film's mystique and eventual reappraisal as a work of art. It had to be discovered and evaluated on its own merits, and when people talk about Blade Runner, very often the first thing that comes up is how audiences of its time just didn't get the film.

Thirty-five years on, we're still talking about Blade Runner - and that's probably the best marketing you can think of.