If there is one scene that sums up this exploration of the futility of the war on terror it is the scene in a bar where Hoffman's world-weary German spy Bachmann confronts a drunken man who has just slapped his wife. Hoffman decks him, only for the woman to tell Hoffman it's okay before embracing her husband. While someone as beaten and cynical as Hoffman shouldn't be surprised at the woman's reaction, it does crystallise the burning question at the heart of this thriller: What's the point?

“To make a world a safer place,” offers Robin Wright's CIA agent who is in Hamburg to oversee Hoffman's operation to ensnare suspected terrorist financier Homayoun Ershadi. With pressure mounting to come up with evidence, hope arrives in the shape of Grigoriy Dobrygin, a Chechnyan Muslim seeking asylum in Germany; his father's inheritance is tucked away in Willem Dafoe's bank and considering it ill-gotten money Dobrygin is looking to cleanse his family name by offloading the windfall to charity. If Hoffman can convince lawyer McAdams to get Dobrygin to take it to Ershadi there might be a temptation for the suspect to funnel the money to extremist groups...

While this adaptation of Le Carre's novel is not as patient as Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, it's just as meticulous; action scenes are absent, plot developments are low key, and the understanding of twists takes concentration. Unlike the measured pace of Tinker... Corbijn and writer Andrew Bovell (Edge of Darkness) keep scenes short and snappy despite the very wordy nature of a screenplay that takes time out to explore the private lives of those concerned.

With its use of unflattering lighting and handheld camera, this is different in style to Corbijn's attractive The American and the harsh black and white Control. However, unlike his use of Manchester in the latter and Castel del Monte in the former, Corbijn can't get across a sense of place despite going to lengths to explain that Hamburg is the front line on terrorism since 9/11. Corbijn's keeps some consistency with his previous films as a theme of desperate people trapped in an aloof world plays out again.

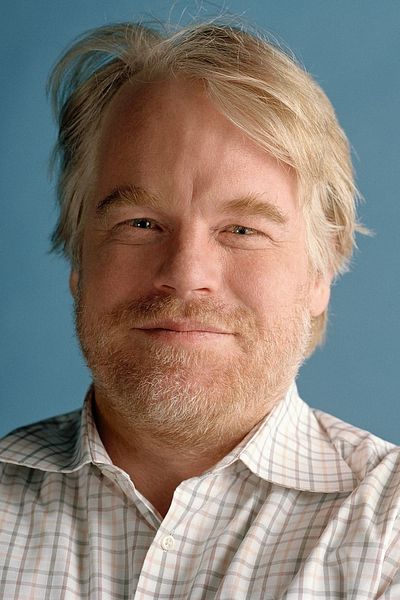

The late Hoffman personifies that very despair brilliantly. With his shifty eyes (he rarely looks at anyone dead on) and his jaded speech pattern, Bachman's harsh, empty life is etched on to his face as he shuffles about waiting for his pessimism to be confirmed.