Once upon a time, Rockstar Games were exciting.

Much like Manchester United in the later years of Sir Alex Ferguson, they were on top of the world.

What Rockstar did, others followed.

The 'Grand Theft Auto' games horrified parents and agony aunts everywhere and became a favourite game of practically everyone.

For a short while, Rockstar could go no wrong.

The anarchic, free-spirited nature of their games faded away as the developers reached the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 era.

It simply wasn't enough for their games to be simply pure fun, their proprietary physics engine had to laboriously simulate real life as much as possible.

Their animation style mandated lifelike models instead of their more memorable striking character designs from the 'San Andreas' era.

As 'Max Payne 3' turns 10 years old, we reflect on the game that set Rockstar down the path of no return.

Payne Relief

Rockstar Games simply couldn't make a purely arcade experience in the HD era, and instead strived for a cinematic experience that sounds better being described than played.

Describing a game where you fly through the air picking off enemies one-by-one in slow motion sounds exhilarating, but in practice, the game plays with all the pace of a World War 2 documentary being played at half-speed.

Rockstar Games had the blessing of original 'Max Payne' developers Remedy to put their spin on the franchise, and on paper the Rockstar boys coming in to take charge of the franchise made sense.

The studio were riding high off 'Red Dead Redemption' in 2010, a supposed wind-down project after the stresses of 'Grand Theft Auto 4' that ended up becoming a smash success.

The development process was anything but.

By expanding on the original liner and modest 'Red Dead Revolver' and making it an open-world behemoth, development ended up spiraling out of control.

A simple project ended up ballooning to a game with a budget of over 100 million dollars, and allegations of crunch were widely reported in gaming media at the time.

A 2010 article from gamesindustry.biz reported that employees at Rockstar were expected to work 12-hour days, including on weekends, to get the game out the door.

A letter signed by "determined devoted wives of Rockstar San Diego employees" pointed to an emerging problem within Rockstar as a whole.

Development of 'Max Payne 3' was similarly troubled, with reports from early 2010 alledging that developers on the game were working under crunch conditions.

A source told Engadget that the game had undergone three rewrites in the space of two years, and that by January 2010 the studio was doing everything it could to release the game in August 2010.

The game would not release until May 2012, amid a wave of publicity, most notably including an advertising slot during half-time of that year's Champions League final.

In their attempt to go Hollywood, the former hellraisers that shook up the world of game design were in danger of believing their own hype.

In our review of the 'Grand Theft Auto Remastered Trilogy' last year we penned an open letter to Rockstar Games:

"For that reason, Rockstar need to reassess their identity; are they the subversive, edgy hellraisers of the game industry that crave column inches and horrify mothers, or have they become part of the bloated elite, comfortable cashing in on fan nostalgia?"

We posit 'Max Payne 3' was ground zero for Rockstar Games losing their edge.

'Red Dead Redemption' was fun to play and had a masterful sense of atmosphere.

The gunplay in 'Red Dead Redemption' was counter-balanced by the serene and haunting quality of the open world that allowed for moments of reflection.

The success of 'Red Dead Redemption' ultimately emboldened Rockstar, and they learned the wrong lessons.

Rockstar took the entirely wrong lessons from the success of 'Red Dead Redemption' and 'Max Payne 3' is patient zero for Rockstar losing their way.

In 'Max Payne 3', if players want to take in the richly-detailed environments, Max makes a smart-ass comment urging players to hurry the story along that it's in such a rush to tell.

Max carries the gun he was using in the prior passage of gameplay into cutscenes, something that must have taken an awful lot of manpower, time and resources to pull off.

While impressive from a technical standpoint, it's a pity Rockstar didn't put as much effort into making the game fun to play.

The pacing of 'Max Payne 3' is akin to someone trying to tell you the plot of a movie they saw on TV at 2 o'clock in the morning with the volume turned down.

Not every game has to be an open-world extravaganza, and if 'Max Payne 3' was released in 2022 it would undoubtedly be an open-world game, but Rockstar put so much effort into making their worlds richly detailed and animated it forgot to make the gameplay fun.

This habit of putting top-end resources into making rich and realised environments at the expense of gameplay is perhaps the lasting legacy of game design of the 2010s.

For all the manpower and hours put into making Max animate like a real person, the gameplay is an exercise in tedium.

The original 'Max Payne' games had a nearly swashbuckling feeling to them, and there was a balletic quality to seeing the detective fly across the room and dispatching of his enemies.

In Rockstar's spin on the character, he moves with all the pace and urgency of an oil tanker attempting to perform a 3-point turn.

There is a narrative justification for it - Max is no spring chicken in this game and the years have caught up with him - but the moment you let a narrative justification get in the way of the player having fun, you've lost the dressing room.

Payne and Gain

'Grand Theft Auto 5' and later 'Red Dead Redemption 2' fell into the same trap.

The Rockstar paradox is one of the great quirks of modern game design; total, unbridled freedom outside of missions, but if you step a foot out of line, the game will fail you out of nowhere.

This started to rear its head in 'Max Payne 3', and it is in service of the story that the game is just bursting to get back to.

And what of this story that 'Max Payne 3' is in such a rush to tell? It borders on self-parody.

In the most recent season of 'I Think You Should Leave', one of the sketches involves Santa Claus playing a fictional detective called Detective Crashmore.

The conceit of that sketch is that Santa Claus is starring in an action movie and delivers hokey and cliched one-liners with no sense of wit or gumption.

'Max Payne 3' is essentially 'Detective Crashmore: The Video Game'.

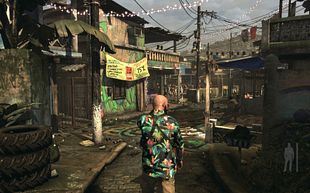

Rockstar stated that the 'Elite Squad' films were a major influ\\\ence on the game, with critics at the time noting a strong 'City Of God' influence on the game.

'Max Payne 3' didn't have the same imagination or intelligence to tackle the socio-economic or political themes those films pull off so elegantly.

Rockstar Games went out of their way to make the story the centre of attention in their game, resulting in unskippable cutscenes.

If players want to replay the game, they have to sit through the same tedious cutscenes with the filter effects that attempt to evoke the vibe of an Abel Ferrara or Michael Mann film but end up smacking of desperation.

Game directors like David Cage deliberately slow down their game to make sure the player take in all the nooks and crannies of their story, and there's nothing necessarily wrong with forcing players down a linear path if the story is good.

For all the hype and pomp surrounding the story, the 'Max Payne 3' story isn't exactly one worth committing to memory.

The subtitle for 'Max Payne 3' very easily could have been 'An Idiot Abroad', whereupon Max stumbles from one situation to the next, all while failing to do his job.

The trope of "I'm taking one last job to get away from my past life" is inherent in noir fiction, but 'Max Payne 3' borders on the farcical.

The gunplay is broken up far too often for the game to slow to a halt so Max can monologue some more about the predicament he's in and he's establishing how he ended up in that particular situation.

Halfway through the game we play through the events that sees Max leave his native New Jersey behind and flee for Brazil.

When the game treads the same ground as the first two games with more modern sensibilities, a bit of colour comes back into the game's cheeks.

In the first two 'Max Payne' games there was a sense of heightened reality with the dream sequences and magic-drug abusing super soldiers, and there was a sense that Max was the jaded straight man to all the antics around him.

In 'Max Payne 3' when everyone else is as jaded and miserable as Max is, the game has all the energy and entertainment value of a bad student film written by someone who gets their life experience from watching bad action movies.

As we saw in 'Alan Wake', 'Quantum Break' and 'Control', Remedy Games have a knack for creating memorable dialogue and interesting characters with layers of motivation, agency and intelligence.

Sam Lake's knack for imitating noire pastiche is made all the more impressive when you play the first two 'Max Payne' games,

When Rockstar Games got their hands on Max Payne, they turned the character into a walking cliché.

In the first two 'Max Payne' games, Remedy leaned into the hard-boiled cop trope, but in 'Max Payne 3', Rockstar believed they were updating the character for the 2010s.

In their attempts to make him come across as a world-weary killing machine like Denzel Washington in 'Man On Fire', they turned him into a self-parody of action movie heroes.

Brazil Nuts

One early line in the game sees Max remark that a location was like "Baghdad with g-strings", which is indicative of the game trying to be a hip Tarantino-style thriller and instead reads like bad fan fiction.

In hard-boiled noir fiction, cheesy quotes being delivered with a sense of conviction is part of the charm of the genre, but 'Max Payne 3' is no Raymond Chandler novel.

Other assorted highlights include quotes like "I might have written the book on bad ideas, but Passos wasn't afraid to quote from it," "I'd killed more cops than cholesterol", and "this town had more smoke and mirrors than a strip-club dressing room."

Modern triple-AAA game writing subscribes to the Marvel-style quippy one-liner school of writing too much for this writer's tastes, but it's possible for a game to come across as irritating when it's trying to be clever.

In taking Max out of New Jersey into the streets of Brazil, the game fails a fundamental test of writing: Are you seeing the most interesting period of a character's life? If not, why aren't we seeing that?

After the events of the first two games, and especially after the controversial ending of 'Max Payne 2', there was a chance to explore how Max became a broken shell of a man and the game does attempt to fill in the blanks of what Max has been up to between games.

Halfway through the game, Max loses his trademark haircut in favour of turning himself into Paul Giamatti after he watched too many John Woo movies.

By that stage of the story, the player is so worn down from the glacial pacing, the hackneyed writing and the game railroading you down one uninteresting location after the next you simply stop caring.

A few weeks after release, 'Spec Ops The Line' was released, and did something truly interesting and unique with its one-man army protagonist.

In 'Max Payne 3', you gun down hundreds of gang members and don't feel a shred of remorse in the game's attempt to make you feel like an action hero.

'Spec Ops The Line' reflects the mirror back at the player and directly confronts the player, asking them why they enjoy mowing down hundreds of enemies over the course of a game.

'Spec Ops The Line' managed to achieve what 'Max Payne 3' couldn't with millions of dollars, high-end technology, and a glitzy advertising campaign; what makes an action hero tick, and why do audiences enjoy watching our heroes mow down people by their hundreds?

Despite spending the last 2000 or so words criticising the game, there are still some high points.

2012 was a vintage year for gaming soundtracks, with 'Hotline Miami' standing out, and Health's score for 'Max Payne 3' is the undisputed highlight of the game.

The scuzzy noise rock adds a layer of character and depth to the game that otherwise isn't there, and nearly becomes a character in its own right.

Great soundtracks can elevate good movies such as 'To Live and Die in LA' or 'Miracle Mile', and the same is true in gaming.

Health's score is a fantastic piece of musicianship outside of the game. and within the confines of the game it's simply breathtaking.

The final big set-piece of the game is a shoot-out in an airport which is when the game comes into its own.

The large, sprawling map takes full advantage of what the console hardware of the time can offer, and as soon as the track 'Tears' kicks in, the entire game up to that point is vindicated.

For all the tedium and slog the player has to endure, the airport shootout is a sparkling example of game design, and having the perfect song play at the right moment is what Rockstar does better than anyone else.

It's a shame it takes the best part of a 'Simpsons' boxset to get to a truly great part of the game.

'Max Payne 3' was sandwiched between 'Red Dead Redemption' and 'Grand Theft Auto 5', and with a decade of hindsight, the game was a dry run for what Rockstar would do with 'Grand Theft Auto 5'.

The weapon selection wheel, the angry protagonist, the minimalist HUD and the scuzzy soundtrack were put before the altar in 'Max Payne 3' and Rockstar used the game as an experiment of sorts.

Not many developers have over 100 million to spend on a game that is essentially a prototype for something that came further down the line, but that is a testament to how big Rockstar were at the turn of the 2010s.

Since then, the developer has become an all-encompassing behemoth, and much like how 'Aliens', 'Terminator' and 'Robocop' were adult-orientated products that appealed to kids, Rockstar have leaned into appealing to the youth demographic.

The next time someone complains online about Rockstar not favouring single-player narratives over live service models, let 'Max Payne 3' serve as a warning.