Star rating: 4 / 5

Review by: Philip Cummins

Venue: Project Arts Centre

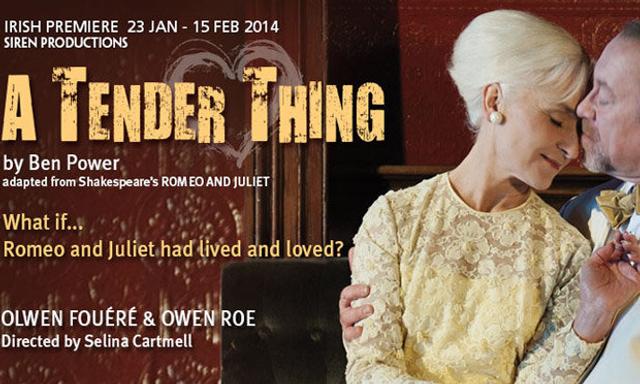

Written by: Ben Power (adapted from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet)

Directed by: Selina Cartmell

Cast: Olwen Fouéré (Juliet), Owen Roe (Romeo)

In his essay ‘Reimagining Shakespeare’, featured in the program for A Tender Thing, Patrick Lonergan states, quite rightly, that “…every generation of theatre-makers and audiences feel the need to reinvent Shakespeare”. The impulse to visually contemporize Shakespeare in theatre and in film - be it West Side Story, or Baz Luhrmann’s 1996 film adaptation of Romeo and Juliet - is testament to the longevity of Shakespeare’s themes: be they love unfulfilled, the downfall of powerful leaders, or health and social issues that remain, in the news, to this day, such as dementia and euthanasia.

The success of A Tender Thing, Ben Power’s daring and visionary adaptation of one of Shakespeare’s most popular and enduring tragedies, is that it somehow manages to remain true to the muscular, romantic and poetic intensity of Shakespeare’s original text, while feeling truly original and fresh with subtle visual dimensions that shine through in Selina Cartmell’s direction and Monica Frawley’s set design.

The set - a bedroom with symmetrical wall lamps and bedside lockers, an en suite, featured upstage left, as well as featuring the central characters dressed in bedclothes - immediately recalls Alan Ayckbourn’s Bedroom Farce, particularly the bedroom of Ayckbourn’s aging married couple, Ernest and Delia, albeit without the hilarity of Alyckbourn’s comedy. While Ayckbourn’s aging couple spend most of their time delivering their lines from their bed, however, Owen Roe (Romeo) delivers his soliloquies with his back turned to a bed-ridden Juliet (Olwen Fouéré).

At the center of Power’s adaptation are two very contrasting performances that encapsulate the central dichotomies of Power’s adaptation. Owen Roe is, quite simply, Romeo as you’ve never seen him: Roe delivers Shakespearean soliloquies in a manner that is unexpectedly natural and unlaboured and much of the verbal force and energy of Power’s adaptation comes through in Roe’s predominantly verbal performance. The opening moments, in which Roe bellows “Give me the light!”, downstage left, grabs the audience’s attention; once that attention is gained, Roe’s performance relaxes into natural, unforced tones that reflect the stripped- down nature Power’s adaptation.

Contrasting sharply with Roe’s nuanced performance is a magnificent and startling performance from Olwen Fouéré. A master-class in physical acting, Fouéré’s brave performance brilliantly articulates Juliet’s terminal decline, while at the same time working closely with Sinéád Wallace’s subtle use of light, which is true to the mostly- silent nature of Fouéré’s performance. Wallace’s lighting, at times, almost feels like another character in the adaptation.

Featured on back on the play’s program is Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, in which The Great Bard writes “Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, / But bears it out even to the edge of doom”. In Ben Power’s slow-burning adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, we get a sense, over 90 minutes, of that doom through a compressed and consistent adaptation, full of imagination and, most of all, heart.

A Tender Thing runs at the Project Arts Centre until 15th February.